Atlantis Dispatch 016:

in which ATLANTIS contemplates the power of thought experiments…

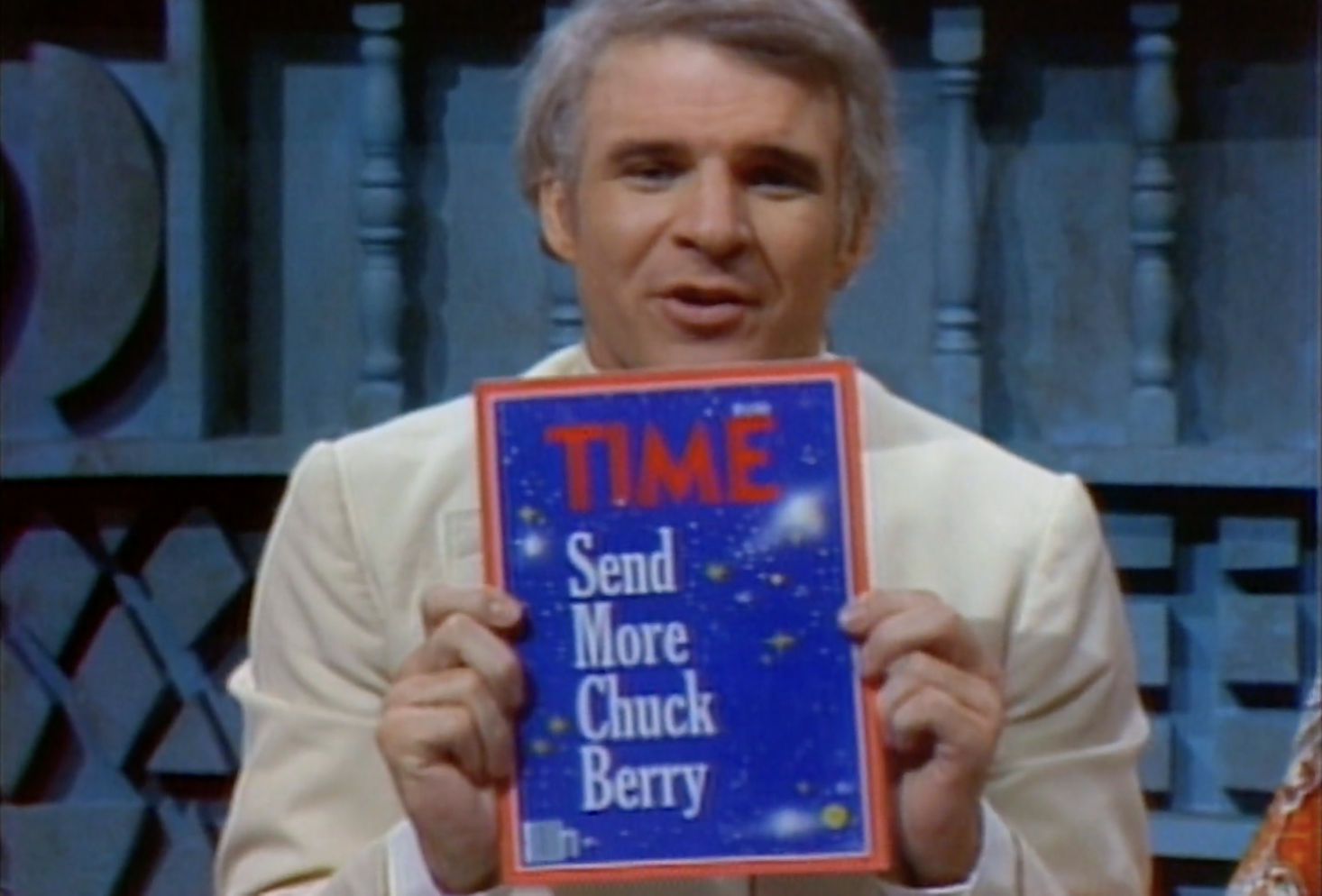

Image courtesy the UFO Museum. Roswell, NM.

March 22, 2022

…begin transmission…

In this season of dispatches from Atlantis, we’ve been delving into the annals of our scientific history to try to recover those ideas from the past that help us find a way into our strange future. And the future, we realized, is coming at us at a rather fast clip. When we stretched out our ocean monocular atop the rising seas, we thought we saw the Future breaching the deep like a great white whale,

“What is it?” Portside said to Starboard.

“A Giant Pacific Octopus?” Starboard replied.

At once we both realized: it is the InterPlanetary Project resurfacing!

As you may or may not know, Atlantis was commissioned by the InterPlanetary Project at a time when only an imaginary sea and space faring craft could safely sail-fly the planet and commune with all of you, our dear readers, without risk of infection in either direction. But, in the days before Atlantis hoisted her virtual sails, each summer since 2018, the Santa Fe Institute has staged a fabulous (fabulist?) ideas festival in the good old Santa Fe Railyard.

What we can see with our monocular as of now is that the InterPlanetary Project is ebbing beneath the surface, and it is about to take a new form. Still festive, still full of ideas, but now a new shape, something at once intimate and global. Woah, you ask, how can that be? Well, stay tuned, as things evolve.

In the meantime, while the InterPlanetary mind lab is brewing up its new creature, we thought it was a good time to return to the Project’s origins and consider from whence we came. In the beginning, the InterPlanetary Festival was conceived as an extraterrestrial thought experiment. SFI President David Krakauer envisioned it this way:

There are two ways you can solve a problem. You can either solve a problem by addressing it directly, or you can ask a much harder problem – and then, en passant, solve the initial problem. Thus, InterPlanetary Project poses a question of galactic dimensions: What will it take to become an InterPlanetary civilization?

Now you might think, in light of the galactic orientation of the project, and Atlantis’s many sailings into space, that this kind of thought experiment is ultimately an experiment about space itself. Au contraire, reader, au contraire.

Instead, it’s more about drastically changing our perspective of the universe in order to rethink our situation as a living planet in the larger cosmos. In other words, the InterPlanetary Project is an imagination invitation. So, what exactly does that mean?

If you’ve attended the live festival, or if you’ve joined in the virtual festivities with Atlantis, then you know that thinking on an InterPlanetary scale doesn’t just help us analyze the specifics of Earth as we know it. Rather, it helps us envision other worlds, other universes, of which we are a living part. If we’re honest, we love other worlds — as Krakauer points out, we often love invented worlds more than the world we inhabit. But perhaps this rival love is really about wanting to do better for ourselves. So what happens when we think about other worlds on an interstellar scale?

There may be as many ways to conjure worlds as there are words, but we thought we’d start with one. Let’s go back to the Sixties, maybe get a little hallucinogenic.

In other words, let’s think on a bit of math our friend Frank Drake presented at SETI’s first scientific meeting back in ‘61: the eponymous Drake equation. The equation says we can calculate the number of alien civilizations in our galaxy capable of communicating with us, if we know:

1) on average how quickly stars form in our galaxy,

2) how many of those stars host planets,

3) how many of those planets could support life,

4) how many of those potentially life-supporting planets eventually develop life,

5) how many of those life-hosting planets develop intelligent life,

6) how many of those intelligent civilizations go on to develop technologies that produce detectable signals of their life,

7) and the average lifetime of those technologically savvy civilizations,

then we’d know how many such civilizations there are today.

Easy!

Well, maybe not.

Here’s an important qualification: this equation, though probabilistically sound, was not necessarily Drake’s attempt to know precisely how many different alien cultures were out there begging for our broadcasts. Like the InterPlanetary Project, the Drake equation was a thought experiment, aimed at inspiring those SETI-skeptics in the room to engage more deeply in a dialogue about alien life detection, generally. And while it was far-fetched thought fodder for that 61’ convention, we stand to learn more about each of these parameters with each year, and with each technological innovation.

Take for instance parameter two: “the fraction of stars that host planets.” In ’61, our sun was the only known star to host any planets. That other stars might host planets was really just an unconfirmed suspicion, a hopeful hunch. Thirty years later, two planetary bodies were found orbiting a distant pulsar, with others detected after that. As of this month, we have confirmed the existence of more than 5,000 exoplanets. Each new exoplanet pushes the likelihood toggle one tick to the right. So, too, as astrobiologists reconsider their notions of “hospitability,” the likelihood of parameter three can grow. Tick, tick. If we find one form of life, we’ll likely find others, and our framework for parameter four changes, too. Tick, tick, tick, and so on until we’re having a dialogue with aliens, instead of about them.

For Atlantis, this kind of thought experiment — the counterfactual — lies at heart of the InterPlanetary Project. Counterfactuals allow us to counter fact, and occasionally what was once counter to fact becomes encountered as fact. Our technologies rise to meet the biggest challenges we face, or better yet, the biggest challenges we assign ourselves. Aim for the stars, right? Or aim back at ourselves, for we are star stuff, too. What other possible worlds might we posit? Is multiplicity somehow essential to envisioning alternative realities? Perhaps it’s best to have a diversity of worlds to consider, in order to reorient our thinking and inspire invention.

In any case, we admire those who dream, just as much as those who prove. While some incrementally probe the universe and thereby probe those pesky parameters, too, we can’t help but also applaud people like our old pal Frank who would rather make a bold first move. By the time our tech catches up to our hope, those interplanetary interlocutors of Drake’s distant dreams might already be traveling back to our place, following his detailed map, and singing along to that golden mix tape he and Carl so carefully compiled for them.